Global Guardian publishes a yearly risk assessment to help corporate leaders and travelers view the global risk landscape and understand country-specific security threats. Our 2025 Global Risk Map spotlights regions and nations where crises are more likely to unfold — potentially leading to future destabilization in an era that may become known as the new Cold War.

|

September 23, 2024 INSIDE THIS ARTICLE, YOU'LL FIND: |

In this year's Global Risk Map, Global Guardian highlights country-specific security risk ratings based on a series of indicators including crime, health, natural disasters, infrastructure, political stability, civil unrest, and terrorism. The map aims to inform businesses and their travelers on the risks they face abroad.

In 2025, the global risk landscape will be shaped by high-level geopolitical drivers and regional challenges. These include overt and gray zone interstate conflict, economic and sectarian-fueled unrest, transnational organized narco-crime, and terrorism — all with the potential to impact multinational organizations and their people. It has become increasingly apparent that the age of polycrisis is among us. There are global issues — intensifying geopolitical competition, economic distress, climate change, and transnational crime — that exacerbate local risks and vice versa. Polycrises along the geostrategic fault lines are set to occur as the new cold war between the new East — China, Russia, Iran, and others — and West intensifies.

With that in mind, Global Guardian’s Geostrategic Stress Index (GSI) — a complement to this year’s Global Risk Map — is a predictive model that shows what countries are most likely to undergo a polycrisis in the next five years driven by geostrategic concerns. This map attributes a low to extreme categorical risk rating that indicates the likelihood of a local crisis taking on regional or global dimensions as countries navigate new cold war relations and the resources for the fourth industrial revolution become more contested.

The Increased Risk Landscape: Regions of Focus

Middle East-North Africa

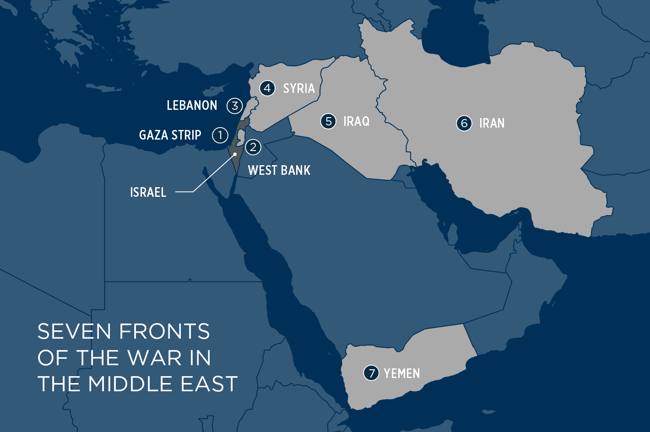

Israel's existential battle against Iran and its “ring of fire” is set to continue into 2025. In July 2024, Israel assassinated Hamas’ political leader, Ismail Haniyeh, in an Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) safehouse in Tehran, and Iran has pledged revenge. This comes as Iran and its web of regional proxies took their war on Israel out of the shadows and into the open following October 7, 2023, with seven live fronts. Israel's regional focus will shift from Gaza to the West Bank and Lebanon, heightening tensions with Hezbollah, while Houthi attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean will persist, forcing ships to take longer, more costly routes. This will further aggravate the ongoing supply chain crisis as shipping demand increases ahead of the busy holiday season later in the year. As we enter 2025, Israel may assess that its strategic window to prevent a nuclear Iran is rapidly closing and choose to act.

The ongoing civil war in Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has created a dire humanitarian situation as ethnically motivated violence is on the rise. The war in Sudan also creates opportunities for foreign powers to increase their influence in the region more broadly and threatens to further destabilize South Sudan and Chad. The UAE's continued backing of the RSF is expected to create tension with Saudi Arabia. Russia, after switching its support from the RSF to the SAF, is expected to establish a naval supply base near Port Sudan in exchange for military aid. This support from Russia will also enhance coordination between Russia and Iran in Africa, aiding Tehran in extending its reach to other nations on the continent that are aligned with Russia.

Latin America

Mexico recently inaugurated its first female President, Claudia Sheinbaum. Like other administrations, she will face challenges reining in cartel violence, corruption, extortion, theft, and kidnapping. As such, security continues to be a top concern in Mexico following the U.S. arrest of Sinaloa Cartel leader "El Mayo". There are also potential political risks should Donald Trump be elected U.S. President in November 2024. Bilateral relations between the U.S. and Mexico could dramatically deteriorate. Trump has promised a mass deportation operation, which could sour relations between the U.S. and Mexico, increasing risks to businesses operating in Mexico. If a new U.S. administration legally designates the drug cartels as foreign terrorist organizations, allowing a wider scope of U.S. action against the cartels, increased violence can be expected, as occurred after Mexican president Felipe Calderon declared war on the cartels in 2006.

Venezuela reopened its longstanding territorial dispute with neighboring Guyana over land west of the Essequibo River in a December 2023 referendum. Since then, it has constructed military infrastructure around the internationally recognized border including a base at Isla Anacoco, an airstrip at La Camorra, and a bridge over the Cuyuni River. In parallel, the Maduro regime also claimed the majority of the Guyana-Suriname Basin, home to more than 11 billion oil-equivalent barrels of recoverable oil and natural gas resources being developed by ExxonMobil, Hess, and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). As the axis of Russia, China, and Iran step up their pressure campaign against the West, the Essequibo dispute could bring a gray zone conflict to the Western Hemisphere.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In June 2024, thousands of young people took to the streets in Kenya to protest a controversial tax bill. The protesters — largely made up of the country’s disaffected youth — were met with heavy-handed policing, including the use of live fire and mass arrests. Despite the security response, protests continued, and the bill was withdrawn by Kenyan President William Ruto. However, the protests had already outgrown that concession, and unrest continued.

The success and tenacity of the Kenyan movement have inspired similar protests or dissent in the other formerly British-controlled countries of Uganda, Tanzania, South Africa, and — most significantly — Nigeria. When taken in the context of the populist coups that took place across formerly French-controlled Africa, these movements portend a generational shift capable of toppling longstanding regimes. In Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, military coups wrapped in anti-French and anti-corruption sentiment have shaken regional stability — and provided an opening for a resurgent Russian presence in Africa. In Senegal, the populist anti-establishment party that incited widespread youth-driven riots in late 2023 were voted into power.

With multiple conflicts escalating across the continent, aging leaders leaving behind unclear successions, and entrenched regimes with dissipating legitimacy, Sub-Saharan Africa now looks much like the North African and Arab world in the early 2010s. While the dynamic unfolding in Africa might not yet merit the label of “African Spring,” a significant change to the continent's political status quo is coming.

Utilizing the Geostrategic Stress Index (GSI)

The Geostrategic Stress Index (GSI) was developed in response to the civil unrest in New Caledonia in May 2024, highlighting how seemingly minor events can reveal larger geopolitical fault lines.

The GSI helps predict where future destabilization may occur in the ongoing new Cold War, where great and middle powers vie for resources, influence, and control. The model assesses various fault lines, from domestic unrest and external influence to the intensification of existing conflicts.

Countries are ranked based on their susceptibility to destabilization over the next 5-10 years, and are classified into risk categories ranging from extreme to low based on their exposure to destabilizing factors.

The destabilization of a country on a fault line could take the form of several interrelated dynamics:

- The exacerbation of domestic tensions or unrest. In New Caledonia, unrest was stoked by Russian and Chinese misinformation regarding French police brutality. The effect this has on a country like New Caledonia is typically greater than a similar practice in a country like the U.K. where misinformation was spread during recent anti-immigration riots.

- A country locked in a frozen conflict could have the conflict thawed by precipitating action from an outside power, as is partially the case in Kosovo.

- Countries experiencing active conflicts could have those conflicts escalated through the funneling of funding through resource acquisition, as is the case in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Or the conflict could be intensified by the direct involvement of a foreign paramilitary, as is the case in Burkina Faso and Niger. Or the conflict could become an outright proxy of another conflict, as in the spillover of the Russo-Ukrainian war into Syria, Mali, and Sudan.

The GSI model is built using four key indicators: the attractiveness for intervention based on strategic resources, security alignment with global blocs, the ability to resist military incursions or influence campaigns, and internal fragility. Countries with rich natural resources or divided security allegiances face heightened risks, especially if they have weak institutions. Conversely, countries with strong military capabilities are better positioned to resist outside interference. Fragility is measured by internal and external grievances and the level of violent dissent.

Key Takeaways

Regionally, Latin America, APAC, MENA, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe each face unique challenges related to geopolitical instability:

Latin America

- Latin America in general fulfills three risk criteria. First, it has an abundance of natural resources providing the incentive and means of funding for aggressive actions. Secondly, it is caught between blocs and has traditionally had to balance American security concerns in the hemisphere with relationships to outside powers. Finally, Latin American countries have relatively weak government institutions combined with relatively robust civil societies, leading to domestic instability.

- Russia, China, and Iran (and Lebanese Hezbollah) all seek to limit American influence in their “backyards” and have consequently established espionage, diplomatic, and military presences in Venezuela and Cuba.

Asia Pacific (APAC)

- The Asia-Pacific region is critical to both superpowers. APAC is also home to multiple middle powers as well as critical industries such as shipping (90% of cargo ships pass through the South China Sea) and integrated chips/semiconductors (90% of the market share for leading edge chips are produced in Taiwan and South Korea.) China has steadily increased its regional influence and the bellicosity of its rhetoric regarding unification with Taiwan, and its claims in the South China Sea.

- Central Asia is at high risk in our GSI. The region is wedged between two of the three main superpowers, Russia and China, and is also an area of key interest for the middle powers of Turkey, Iran, and India. The United States and Europe have made increasing overtures aimed towards economic and political development in the region to mitigate Russian and Chinese influence. Stability in the region largely depends on how the Central Asian states can manage to play both sides. Moreover, Central Asian regimes are susceptible to economic shocks which can quickly translate into violent unrest as seen in Kazakhstan in 2022.

- Southeast Asia is also at high risk. The ongoing dynamic conflict in Myanmar and perennial political crises in Thailand threaten to shake up the political alignment of the region, which is critical to Chinese interests. In the context of the efforts of the Philippines and other U.S. partners to contain China in the South China Sea, localized conflicts in Southeast Asia carry the potential to quickly translate into globally significant flashpoints.

- The Pacific Islands (including territories without data) will face increasing destabilization in the medium to long term.

Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA)

- Our model predicts that the Israel-Palestine Conflict will continue to be a major fault line.

- With a high concentration of Middle Powers and strategic resources, namely fossil fuels, the region's instability is predicted to continue.

Sub Saharan Africa (SSA)

- Sub Saharan Africa is emblematic of the destabilizing effects of the world’s present polycrisis. Epidemic health issues have combined with insurgent Jihadism and climate change to produce a tenacious set of interconnected issues made more intransigent by the inability of great powers to cooperate. In multiple countries the region has already become a proxy theater for the Russo-Ukrainian war, with both states sending special forces and military aid to competing sides.

Europe

- In Europe the main potential flashpoints rest in the Balkans. Ethnic tensions in Kosovo, as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina, threaten to pull Serbia — and its main traditional ally Russia — into a more direct conflict with NATO.

- The complicated relationship between the European economic aspirations of regional actors and their domestic imperatives lays out a viable path to civil unrest, gray zone aggression, and possibly, military confrontation.

- The region’s geographic and cultural situation in between Russia and NATO make it a natural point of friction and key battleground in the New Cold War.

How Businesses and Travelers ShoulD Prepare

The past few years have demonstrated the profound effect that exogenous events can have on business. Personnel have been endangered or detained by changing relations in China and Russia. State-backed hacking groups have stolen billions from private enterprises. Supply chains have been repeatedly imperiled by a pandemic, the wars in the Middle East and Ukraine, extreme weather events, and even errant ships in the Suez Canal and Baltimore harbor. The 2025 Risk Map can help risk management identify gaps and vulnerabilities to make more informed decisions to keep their personnel, assets, interests, and bottom line safe.

Furthermore, businesses and organizations can use the Geostrategic Stress Index (GSI) as a vital tool for future planning by identifying regions where geopolitical instability is most likely to emerge. By understanding the factors that contribute to a country’s risk level — such as resource vulnerability, external influence, and internal fragility — companies can anticipate potential disruptions in their supply chains, market operations, and investments. The GSI allows businesses to strategically allocate resources, diversify operations, and develop contingency plans for navigating politically volatile environments. In an era of converging global threats, this forward-looking approach can help organizations mitigate risks, protect assets, and maintain stability in uncertain times.

Utilizing these resources, organizations should organize tabletop exercises with key stakeholders and established vendors, and ensure business continuity plans are in place and responsive to these risks and fault lines. Navigating this landscape requires more than reactive planning. Enterprises must proactively assess their exposure to geopolitical risks, understand how these dynamics converge, and stay aware of global hotspots.

Bellicosity and its consequences are no longer the domains of states but of all enterprises that rely on stability in everything from sourcing, operations, and market access. It is incumbent on corporate decision-makers to walk through the “what-if” and explore various scenarios that could arise from the current threat landscape to promote resiliency, business continuity, and, ultimately, protect the workforce.

Global Guardian's annual Risk Map displays country-specific security risk levels based on a series of indicators including crime, health, natural disasters, infrastructure, political stability, civil unrest, and terrorism.

This year's addition, the Geostrategic Stress Index (GSI), attributes a low to extreme categorical risk rating that forecasts the likelihood of a local crisis taking on regional or global dimensions as countries navigate new cold war relations.

To download your copy, complete the form below.